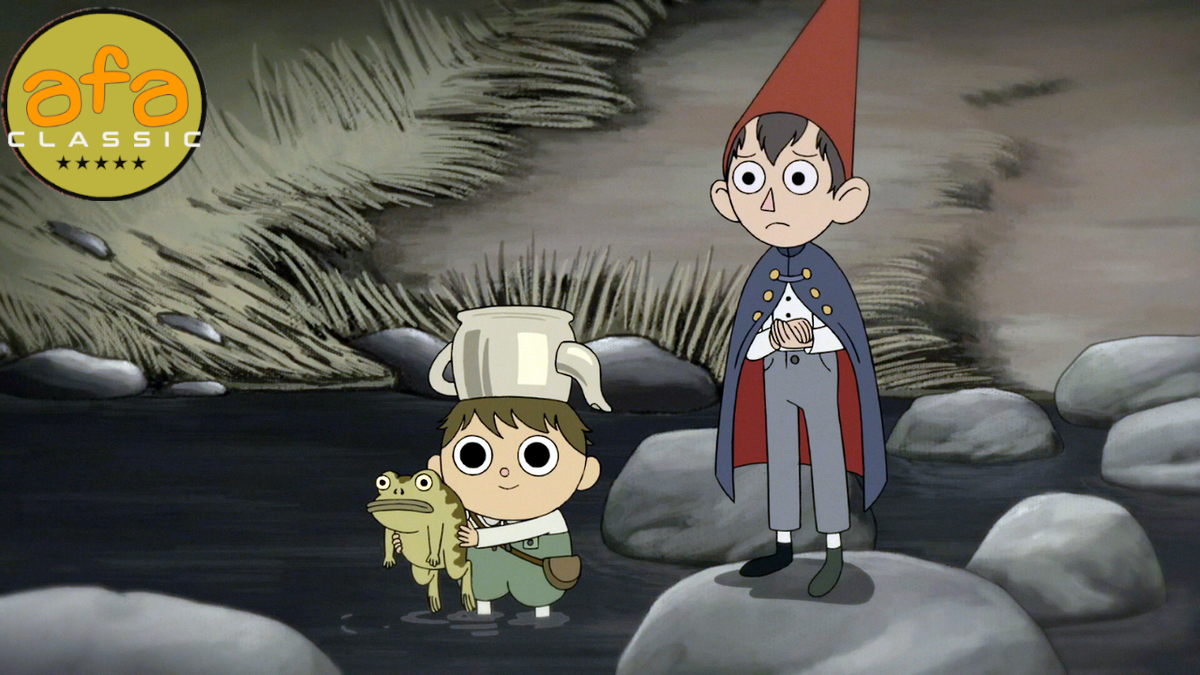

Over The Garden Wall (2014)

Along the way, they meet Beatrice, a cantankerous talking bluebird who is drawn to the boys for mysterious reasons. Each episode depicts the group stumbling into a new clearing, town, or cottage in The Wood looking for a way home. Instead, they find people from a variety of eras with clandestine or simply inscrutable goals and needs. There’s a Gibson Girl teaching animals to read, a Betty Boop-inspired keeper of an 18th-century tavern, a Puritan-era witch and her waifish ward who speak in thees and thous. And throughout it all, the sinister and eloquent Beast, “the Voice of the Night,” haunts their trail in an effort to break their will. A creature of shadows, horns, and tricks, this antagonist is one of the most hair-raising and bone-chilling in all of animation. The Beast’s evil machinations are only kept at bay by the forlorn but well-meaning Woodsman.

This miniseries debuted on Cartoon Network during Halloween week of 2014, segmented in two 11-minute installments a day. About the length of a feature film, the miniseries has made its way into many folks’ Autumn favorites (I have rewatched it every October for several years myself). It boasts an impressive cast: Wirt is played by Elijah Wood, the Beast by Samuel Ramey, and secondary characters are played by Tim Curry, John Cleese, and Christopher Lloyd, among others. It might seem odd that so many large names (particularly those that the average intended viewer is too young to recognize) found themselves in a one-off Halloween miniseries. But with one viewing, it becomes apparent why this show would appeal to a more mature audience.

Over the Garden Wall rejoices in the macabre underbelly of New England Americana aesthetic and in European folklore. The subtle but distinct allusions to an austere and intense flavor of religiosity, as well as the overarching motifs of death and decay, bring out the vibrant, funny, and musical matter that takes center stage. The gorgeous natural landscapes exemplify the kind of beauty so many of us look forward to in the Fall, but not without reminding us what the season means to us symbolically: mortality, permanent transitions, and of course the terrifying power nature holds over our lives. The half-moon that hangs over every shot of the night sky acts as a reminder that Wirt is going through a change: not just as a leader who can find a way home for him and his little brother, but as a child becoming a teenager, and someone who can face new challenges, the unknown.

Over the Garden Wall is unapologetically metaphorical: drawing off its roots in folklore, each episode dips into fable-like moral discussions that center around the theme of embracing, or taking on something that is unknowable and scary. But it’s also aware of its cultural context - 2010s audiences didn’t care much for neat little aesops on TV. And who can blame us? We were tired of sanitized lessons that demanded nothing of us intellectually or practically, and that seemed manufactured by corporations for the main purpose of making their commercialism seem palatable, morally-neutral. Over the Garden Wall’s most prestigious contemporary Adventure Time was iconic for its enigmatic themes and mistrust of anything too black and white.

The simple shapes each character is comprised of work oddly well with the complex painted landscapes (I’m having horrible flashbacks to the dead-eyed and wooden characters of Castlevania.) An impeccable color pallette and strong designs keep these disparate amounts of detail cohesive. Further, these simple shapes (completely unlike Castlevania) move fluidly and expressively. Despite the show using a wide variety of storyboarders (including Natasha Allegri and Pendleton Ward), designs are fairly consistent. This leads to some wonderfully tense moments, such as The Beast sliding stiffly into frame from behind a tree or the pupils of a man on the edge of madness (Cleese) suddenly dilating. In one remarkable scene, a character performs a number in a Cab Calloway, Fleisher Brothers-inspired style that mimics the uncanny effect of rotoscoping, maintaining the unsettling perspective without any of the goofy sloppiness that rotoscoping usually features.

Over the Garden Wall was a part of McHale’s life since 2004, and as some old fable about a turtle and a rabbit or whatever teaches us, slow and steady wins the race. In fact, the inexplicable black turtles that can be found throughout the series could be read as a comment on this: slow and meticulous progress through life might seem like a cumbersome bore, but it can contribute to truly incredible success. McHale has not lead his own project since this miniseries, and with any luck, that means he’s been occupied with some new idea that’s been working its way into a fully realized form for nine years. Or maybe, this piece was all he had to say through the medium of animation, and he’s happy to continue working on other projects. The latter possibility is a bit sad, sure, but I know that I’m ready for the unknown.

★★★★★

Shain Slepian is a screenwriter, script consultant, and content creator with a life-long love of animation and media analysis. Their work can be found on Medium, Left Voice, and on their YouTube channel, TimeCapsule. Shain's book, Reframing The Screenwriting Process, is available on Amazon.