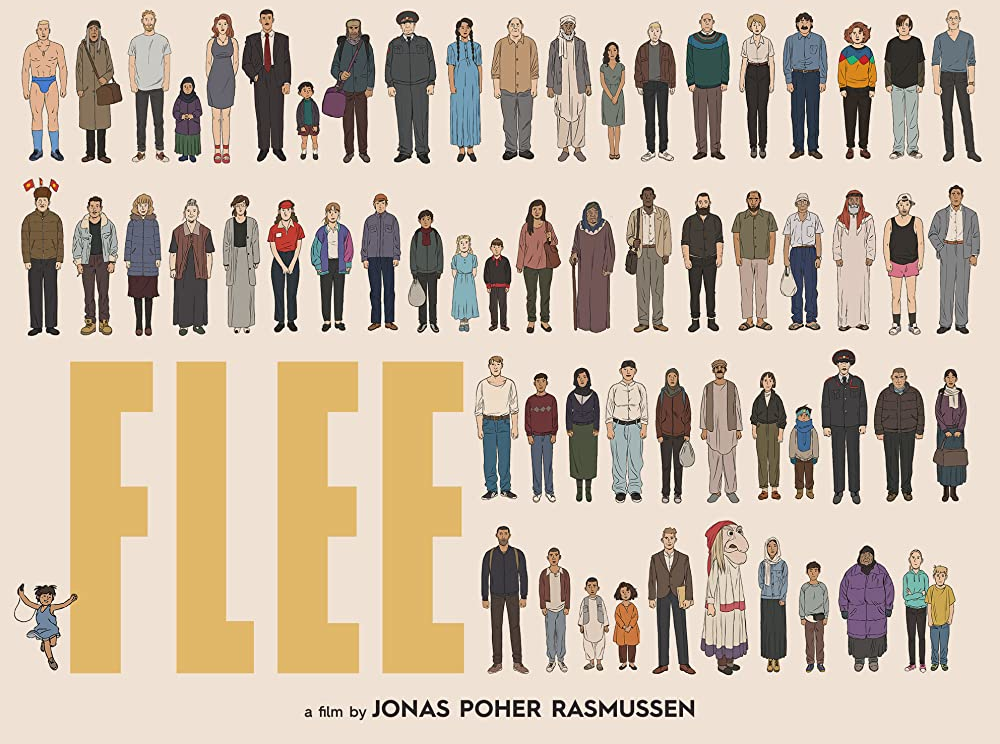

Flee (2021)

On television, adult animation has kept pace with the zeitgeist in recent years,

with landmarks from Rick and Morty to BoJack Horseman. But in the

cinema, Flee is the first plainly adult animation to garner mainstream

attention since Waltz With Bashir back in 2008. (You could argue for the

likes of Don Hertzfeldt’s It’s Such a Beautiful Day, or

Charlie Kaufman’s

Anomalisa,

but they feel more like critically-lionised cults.) TV adult animation is

usually farcical. It has no link to Bashir and Flee, which are both

documentary-testimonies about grim man-made tragedies. Adult animation shouldn’t

be a genre, but it looks like two demarcated ones on the big and small screens.

Yet Flee is far from a clone of Bashir. In contrast to its predecessor’s

collage of viewpoints, Flee is the focused story of an Afghan boy,

Amin, who becomes a refugee after Kabul falls to the Taliban in 1989.

Flee shows not a battlefield, but rather a living limbo. Much of the film is

set in a broken-down Moscow after the Wall fell, where Amin’s family contends

with new terrors. There are sadists in uniforms banging on doors, human

traffickers funnelling the desperate into cages over dark water, where noone

marks your drowning. And occasionally, we who’ve never known exile see

ourselves – looking out indifferently over spaces that are so small, yet are

unbridgeable to those on the wrong side.

We know from the outset that Amin will live. He’s relating his story in

flashback to Danish director Jonas Poher Rasmussen, who he befriended

at high school. This was after the ordeal, which Amin kept private for many

years, for reasons revealed slowly. The film shifts from present to past

without fancy tricks. The early scenes highlight Amin’s act of remembering as

the creation of the film, as a similar act was shown in Bashir.

At first, Flee’s tone can be light. In the opening minutes, the infant Amin

scampers through Kabul’s streets in a dress while listening to A-ha’s

Take on Me, a song that has its own

place in animation

history. He’s like the heroine Marjane in Persepolis when she

was a jumping bean child, striking Bruce Lee poses and chatting with

God. One of Flee’s biggest unburdened laughs is when Amin remembers his

childhood crush… on Jean-Claude Van Damme, winking at him from a

poster. The present-day Amin needn’t hide his orientation, as he had to

growing up in a culture with no word for homosexual.

Yet even the adult Amin is withdrawn from his loving husband, and snaps at the

director when he probes how Amin’s past shaped him. Through the film, we see

how this mindset was formed: by forced marches with the unvarnished threat of

murder, by oppressors who held absolute power, by a system that made Amin deny

his family to save himself. One of the film’s worst atrocities takes place

just feet away from Moscow’s inaugural McDonalds. Even in “safe” countries,

there’s fear. Near the film’s end, a family member drives Amin to an unknown

place, and the journey feels as chilly as Moscow.

It’s a powerful account, delivered clearly, and that’s enough to make Flee a

success. But the delivery is only aesthetically outstanding in short

bursts.

To call Flee animation is somewhat misleading. It’s a multimedia project

that’s often held together by live-action. Other animated documentaries,

including Bashir, use live-action for crucial effects, but it runs through

Flee like letters through Blackpool rock. This is archive footage, showing the

places and events that the characters pass through; the swinging Kabul of

Amin’s infancy, the collapsing Moscow of empty shelves and hyperinflation. As

in Bashir, there are glimpses of uncensored death (in footage of the fall of

Kabul.) Occasionally live-action cuts into the story more directly, to give a

sense that Amin or his family were here, at this precise moment. The animated

characters never get superimposed over live-action, but they seem just out of

shot, so that we superimpose them in our heads.

The live-action footage comprises one of Flee’s three modes of representation.

The second is impressionist animation of the kind you often see in festival

shorts: flickering human outlines on the brink of dissolving into an ocean of

churning lines and brushstrokes, faceless figures that are overtly universal,

archetypes standing for huge masses of people through the world and history.

One early flashback depicts the arrest of Amin’s father, not by the Taliban

but by the previous Afghan regime. The figures in this flashback are avatars

of oppression, resignation and grief. (The grief is the wife’s, who stands

helpless at the scene.) By sheer coincidence, it matches a crime described in

a new live-action film, Pedro Almodovar’s Parallel Mothers, which has a

subplot about the Spanish Civil War. This coincidence only highlights the

universality of these scenes, far beyond Amin and Afghanistan.

But the evocative sequences are very short, lasting just moments, Beyond the

specificity of the live-action and the universality of the abstract images,

there’s… the rest of the animation. This has simple cartoon characters who

don’t move so much as judder. The frame rate is one of the lowest I’ve seen in

an animated feature, the epitome of functionality. It’s enough to tell Amin’s

remarkable story, but it feels almost devoid of artifice.

Occasionally there’s a nuance, of the kind you might find in a TV anime with

similarly functional animation; for instance, a cut to the child Amin’s

worried face as his brother promises to make him a real man. There’s room

for unforced motifs; flying as escape (birds, aeroplanes), and two treasured

objects that root Amin’s life, a wristwatch and necklace, that mark

different phases of his growth. But in a truly weird irony, the liveliest

non-abstract animation is found in a campy dubbed Mexican melodrama that

Amin’s family watch blankly on TV while hiding in their brother’s apartment.

The backgrounds are far more evocative. The paintings of the plains and

mountains around Kabul deserve a cinema-sized screen. Later, there’s a

sequence where the characters are forced through a forest at night, and now

it’s the primal background, the sinister trees and the darkened treacherous

path, that make the crowd moving jerkily down it seem real.

That leads into the film’s most terrifying scene, indeed its defining one.

Amin and his family are packed into the hold of a tiny boat with dozens of

other men, women and children. We know the situation from the news; now Flee

lets us glimpse how it feels, the awful sound of water against a groaning

hull, the closeness of an unbelievably horrible death. And yet… the scene is

mostly illustrated radio. So much of its power is carried by the sound, and

by the adult Amin’s spare commentary and so little of it depends on the

crude images… until the sequence briefly plunges into impressionism, as Amin

contemplates the reality of drowning.

When evaluating animation, I tend to go by what British animation legend

Bob Godfrey told me once; that the animation is never more important than what the

film-maker is putting over. When I first saw Flee, I found many of the early

scenes, which are often people just talking, unbearably clunky. It was

impossible to ignore the myriad different ways it could have been animated

better, more insightfully, more creatively. (As a British viewer, I flashed

back to Aardman’s early

Lip Synch films, the ones

that weren’t Creature Comforts.) Once Amin’s story took over, I found

the animation far less distracting, but on rewatching the film, I found the

limitations loomed greater again.

I don’t find Flee as compelling as Waltz With Bashir, which has a looser

narrative, but many indelible moments, or Persepolis, a less harrowing story

of exile that’s still powerfully sad. I also prefer the “Young Adult”

fiction tack of

The Breadwinner,

the Taliban drama by Cartoon Saloon, threaded through with fantasy.

Flee’s story is amazing; its telling is often no more than substantial. It

amounts to a good film, but not, I think the milestone that some have called

it.

★★★★☆